Recorded in: Chicago, IL in 1972

Episode Length: 1:08.14

Air Date: August 8, 2018

Interviewed by: Danny Lyon

Produced by: Jordan Weitzman

Edited by: Cristal Duhaime

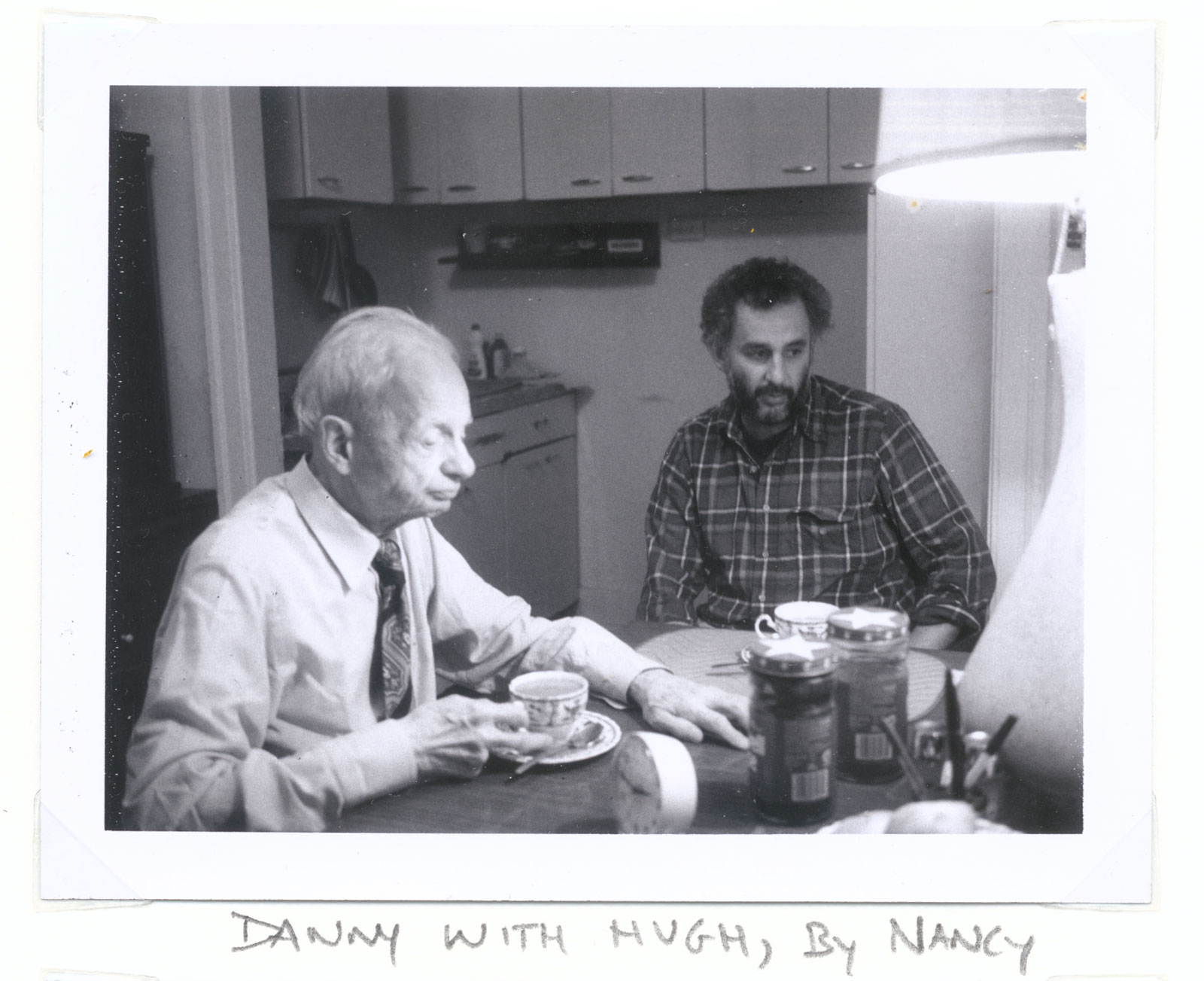

In 1972, more than a decade after I had taken up photography in earnest, I returned to Hyde Park to visit with Hugh Edwards. By then Edwards had retired from his position as Associate Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago and was teaching a night course in the history of photography at the School of the Art Institute. Because Hugh Edwards did not like to be photographed, there aren't many photographs of him. He also didn't want to be filmed or tape-recorded—claiming, in his words, that he did not want to be "etched in concrete." He also hated to write, and did so reluctantly and infrequently. I had come to Chicago intent on making tape recordings of him, in order to try and preserve the astounding ability he had with language. Almost everything he said was laced with irony and wit. His reading and his contrary thinking about almost everything in society made him the most intellectual American I had ever known.

Well aware of Hugh's reluctance to be documented for posterity, I told him only that I wanted to record something about his parents and his background; I knew that Hugh had lots of vivid stories about his childhood. Born in Paducah, Kentucky, in 1903, Hugh had been stricken with a terrible and painful bone disease in his infancy. He had to be wheeled around in a cart by his parents until the age of six. (He would be lame for the rest of his life; in the Print and Drawing Room at the museum, there was always a pair of wooden crutches leaning against the wall next to his desk.) One of his ancestors had come to America from Ireland and built a hotel deep in the Tennessee woods after marrying a Cherokee Indian. His mother had worked in a post office near the Ohio River where his father, an engineer on a steamboat, first met her. During the Battle of Shiloh, which was fought just below the border of western Tennessee—a battle General Grant later described as being so ferocious that you could walk across the field by stepping from one dead body to the next—Hugh's great-uncle was shot in the head with a minie ball.

Hugh's grandfather and his grandfather's younger brother, accompanied by a slave named Toby Arnold, then walked to the battle site to find him and bring him back to Paducah. As a child, Hugh was able to lay his finger in the dent that the ball had left in his great-uncle's skull.

When Hugh was a grade-school student, there was a lynching in Paducah. Because Hugh's father was a socialist, some of his classmates left a piece of the victim's skull inside Hugh's desk, to torment him; when the boy opened the top and reached inside, he touched it.

The truth was that I had come to Chicago to try to record Hugh's ideas on photography. Hugh had discovered me when, as a boy of nineteen, I had put a photograph of a construction worker in a University of Chicago Arts Festival contest—and, the following year, a photograph of a truck in the desert. I still remember that spring afternoon when Hugh came into Ida Noyes Hall to see the pictures that were hanging there. The rain was coming down in sheets as he swept into the hall, and I watched as the little man in the Kangol hat propelled himself up the short flight of stairs on his two wooden crutches.

He awarded my picture first prize. The other judge was the former documentary (and later abstract) photographer Aaron Siskind, who challenged Hugh's choice and said he "didn't like trucks." Hugh countered with, "What do you like, pregnant women?' Perhaps there was a picture of a pregnant woman in the show.

It was Hugh who passed on to me his enormous admiration for certain photographers, and inspired me with the feeling that there was so much that could still be done. In 1965, he loaned me his Rolleiflex, which I took into Uptown in 1967, and again in 1969, he gave me one-man shows at the Art Institute.

At the time, I think I printed and edited my pictures so that I could bring them to Hugh for him to look at. After he died, I thought, "Now who do I show the pictures to?”

But what were these ideas that had apparently affected me so? Where did they come from? I had never really encountered anyone in the field of photography who spoke the way he did. My idea that winter was to make "one hundred tapes." In fact, I made only three, and I recall being very disappointed with them afterwards. He sounded so stiff, at times academic, not the person I knew at all. Hugh took it all very seriously. I was so disappointed in the result that I did not listen to the recordings again for twenty years.

Hugh Edwards died in 1986. Six years later, when I was editing his letters, I took out the five-inch reel-to-reel tapes and played them on the same Nagra I had used to make them in 1972. I was stunned. There he was —the laconic Southern accent, the shyness, the irony, the brilliance. I felt like picking up the machine to see if he was hiding beneath it. Hugh liked to say, "the best dialogue is a monologue." He was right.

- Danny Lyon

Links:

https://bleakbeauty.com/picture-essays/hugh-edwards/hugh-edwards-letters/

http://media.artic.edu/edwards/